Now that COVID-19 is subsiding, global aviation traffic is recovering and ready to resume growing in the years to come. The strain of this growth on the world’s Air Traffic Management (ATM) system has been recognized for years, which is why aerospace bodies such as ICAO, Eurocontrol and the FAA are championing a new ATM system called Trajectory Based Operations – TBO, for short. If successfully implemented, TBO will replace the current piecemeal, fragmented approach to ATM with a rational, coordinated system that will increase usable airspace capacity while streamlining flight management, enhancing safety and reducing aircraft emissions. This ‘TBO Primer’ aims to distill a complex concept into clear and simple terms.

What TBO Is

Trajectory Based Operations uses the flight trajectory of every in-service aircraft in four dimensions (4D) – latitude, longitude, altitude, and time — to ‘know’ their 4D positions at any second of linear time. It then uses this data to manage the airspace more effectively.

To make this happen, “The trajectory is defined prior to departure, updated in response to emerging conditions and operator inputs, and shared between stakeholders and systems,” explained the FAA TBO web page (/www.faa.gov/air_traffic/technology/tbo). “The aggregate set of aircraft trajectories on the day-of-operation defines demand, and informs traffic management actions. A ‘day-of operation’ refers to operating conditions during the day an operation takes place, including equipment outages, weather, airport conditions, airline delays and cancellations, and other temporary conditions in the NAS (National Airspace System).”

According to Airbus, TBO can reduce the inaccuracy of current ATM prediction models by approximately 30-40 percent. This level of improvement, plus TBO’s ability to safely manage more aircraft flying within the same airspace, explains why the concept is so compelling to players in the civilian aerospace sector.

“TBO’s purpose is to smooth airspace and airport demand by managing the entire trajectory of all aircraft in four dimensions ‘from gate to gate’,” according to Michael Bryan, founding principal and managing director of Closed Loop Consulting.

The image on the left illustrates the current inefficiencies of ATC. Notice less direct routes and some aircraft holding before landing.

The middle image shows the TBO workflow.

The image on the right shows the more efficient method of travel for aircraft using TBO.

Closed Loop images.

“Fundamentally, TBO’s purpose is to smooth airspace and airport demand by managing the entire trajectory of all aircraft in four dimensions ‘from gate to gate’,” said Michael Bryan, founding principal and managing director of Closed Loop Consulting, a global aviation industry consulting firm. “Its concept seems utopian, but it’s entirely achievable if airlines, air navigation service providers and their industry bodies get on the same page.”

Sharing, Maintaining, Using

Henk Hof is head of Eurocontrol’s ICAO and Concept Unit. He is also chair of the ICAO ATM Requirements and Performance Panel (ATMRPP). This panel developed the TBO concept under Hof’s leadership, and is developing it further through standards and guidance.

According to Hof, TBO is based on three simple ideas: “Sharing of flight information including the 4D flight trajectory between all actors involved in managing the flight, maintaining the flight information at all times during the flight, and using this flight information for collaborative decision making,” he told ATR. “It all comes down to three words: Sharing, Maintaining and Using.”

These three words encapsulate an ATM concept that is truly breathtaking. TBO integrates all aspects of civilian flight management into a common shared platform — one that is designed to deal with unexpected delays and events by addressing the needs of everyone affected by them, rather than leaving it to flight crews and harried air traffic controllers to sort things out on the fly.

This is a true paradigm shift from the way in which ATM is being done now. “Today, you can think of ATM operations as being like a group putting together a puzzle when nobody can see the full picture on the front of the box,” said John Bernard, lead for L3Harris Technologies Mission Networks’ Advanced Concepts Engineering Team. “Each player pretty much knows how their own pieces fit together, but as they’re trying to assemble the broader puzzle, they can only talk to the other players about their respective pieces to try and understand the bigger picture, because they can’t see it themselves. In contrast, TBO hands everyone the lid on the box so they can see how their pieces fit into that picture.”

When everyone can see the picture on the box, everyone can work together to put solve the puzzle. The same is true for ATM under TBO: When all players in civilian air transport can work together to plan, execute, and adjust collective flight trajectories, delays, fuel wastage, and risks are reduced while aircraft throughput and on-time arrivals/departures are increased.

What TBO Has to Offer

At the highest level, TBO is superior to current ATM because it is a ‘clean sheet’ system. In contrast, “ATM today is very much an extrapolation from the past,” said Hof. “Everything is more or less the same but a bit better.”

“With TBO, we changed the approach,” he continued. “This is because TBO is built upon principles such as System Wide Information Management and FF-ICE (Flight and Flow Information for a Collaborative Environment). These TBO principles will enable automation to support Collaborative Decision Making (CDM) by all TBO players during all phases of flight. They will allow traffic flows to be optimized and conflicts to be anticipated and solved. They will reduce the need for tactical interventions and increase the efficiency and capacity of the whole ATM system, while reducing the cost of it.”

“Without TBO, conventional ATM will eventually reach the limit of its capability,” says Michael Bryan, founding principal and managing director of Closed Loop Consulting. FAA graphic.

TBO’s support of CDM is what makes this system to superior to current ATM. “With TBO, all of the stakeholders will understand in detail what is happening tactically, enabling improved strategic decision making,” said Bernard. “Likewise, with improved understanding being provided at a strategic level, controllers and aircrews can collaborate for more effective tactical decisions.”

A case in point: If an aircrew flying within a TBO ATM regime know that they will be delayed in landing due to an emergency at their destination airport, they can work with air traffic control to slow down their flight, absorbing that time delay en route while burning less fuel while doing so. As well, all airlines flying in this airspace will be able to adjust their own flights based on this TBO data, working with ATM to use slower, more fuel-efficient routes.

TBO’s level of integrated control also allows airlines to make more informed decisions in route planning and management, and gives ATM the ability to move beyond reacting to changes in their respective airspaces as they occur. Most importantly, TBO allows the players in civilian air transport management to work together as a team using a shared information platform, rather than players with conflicting interests working with limited, unshared data. John Bernard’s ‘puzzle box’ analogy underlines this benefit neatly. When everyone can see the whole picture, everyone can work together to their mutual gain.

That’s not all. By allowing more aircraft to fly in the same airspace safely, TBO positions ATM to safely manage the growth of civilian air traffic going forward. Like the radio frequency (RF) spectrum, airspace is a limited resource. The only way to fit more traffic into either of them is by finding better ways to do so. In the RF spectrum, the answer has been digital data compression and smaller transmission footprints to support 5G wireless service. In aviation, co-ordinated end-to-end traffic management through TBO can deliver the same kind of expanded usage in a similarly finite space.

“TBO brings macro benefits to the industry that conventional air traffic management (that’s Air Traffic Control) cannot achieve,” said Bryan. “Without TBO, conventional ATM will eventually reach the limit of its capability.”

This last point matters. When it comes to ATM as it now stands, “the current system is not scalable,” said Hof. Moreover, the infusion of drones, unmanned air taxis, commercial space vehicles, High Altitude Aerial Platforms, and hypersonic aircraft into civilian airspace only adds to the ATM challenge. “Bringing all these different types of vehicles and operations together requires a more advanced way to manage the mix than is done today,” he noted.

L3Harris’ Bernard cites a slew of other benefits associated with adopting TBO. “First, there are the economic benefits of improving efficiency: Savings on flight times, shorter routes, more predictable arrival times — all reduce costs associated with aviation,” he said. “TBO also increases system capacity, enabling more flights.”

“Second, climate change is increasing societal pressure on all forms of transportation to improve efficiency, including aviation,” continued Bernard. “TBO improves both per flight and overall system efficiencies through the various mechanisms already discussed, driving down aviation’s carbon footprint.”

“Finally, technology is evolving rapidly with a focus on leveraging large data sets to improve decision making and reveal previously unknown opportunities,” he concluded. “Aviation is no different. TBO is the key step to improving data exchange and enabling an information-centric aviation system that can take advantage of new technology like artificial intelligence and autonomy moving forward.”

Is TBO Achievable?

From all angles, Trajectory Based Operations appears to be the next logical step for ATM worldwide. But there’s a big divide in life between what should happen and what could. TBO has already proven itself in the first category; where does it stand in the second?

Let’s start with the regulators. “We developed the TBO concept in ICAO and will start with the development of further guidance,” said Hof. “In Eurocontrol, we are implementing FF-ICE release 1 (‘Flight & Flow Information for a Collaborative Environment’, the translation of the TBO concept into an actionable plan; available http://www.icao.int/airnavigation/ffice) and are deeply involved in R&D on TBO. TBO implementation is a phased process that will take several years.”

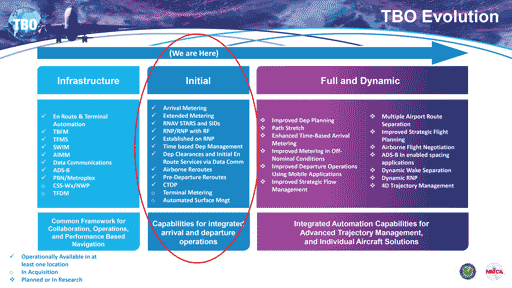

In the United States, “The FAA is delivering decision support for TBO through evolving enhancements and integration of two legacy and one new automation platforms: Traffic Flow Management System, Time-based Flow Management, and Terminal Flow Data Manager,” according to the FAA. “Also known as the three T’s, these systems help strengthen strategic planning and resolution of capacity-to-demand imbalances throughout the day-of operation.”

This said, disparities in ATM budgets between the ‘developed world’ and Third World nations means “implementation of TBO, while interoperable, will not be the same in all states,” said Hof. The good news: “Eventually TBO will become the norm and it will be more expensive to maintain old legacy systems than change to the state of the art. But this will take some time.”

Of course, to deploy TBO on a meaningful basis globally (even if only in the busiest air corridors), “communications must be improved across a variety of boundaries,” Bernard said. “Aircraft to aircraft, aircraft to ground, ANSP (air navigation service provider) to airline, ANSP to ANSP across national borders — these boundaries and the limitations of today’s information exchange across them are the challenges TBO must solve.”

L3Harris is helping the FAA address some of these TBO challenges. The company’s assistance includes providing Data Communications (Data Comm) services to the FAA to modernize air-to-ground links between pilots and air traffic controllers; enhancing ground-to-ground information exchange between the FAA, airlines, and other stakeholders through the System Wide Information Management (SWIM) program; and assisting the FAA with ADS-B and related services as part of the Surveillance Broadcast System (SBS) program.

Still, there are several obstacles that have to be overcome to make TBO a reality. For instance, “While the concept is quite mature and some ANSPs have reached a point where they are ready to begin applying it, there are too many differences in perception about what it really is in other parts of the industry,” said Michael Bryan.

As for the technology to support a TBO rollout? Some of the necessary elements such as SWIM has already been deployed, Bryan noted, while “FF-ICE, the penultimate step for the ANSP-side of the problem, is being trialed, although perhaps too quietly. Other components that rely more on the airline side of TBO, such as PBN (Performance Based Navigation), have been around for years, but global uptake is still just over halfway there. Overcoming airline inertia is a hurdle for most global initiatives. The airline side simply takes too long to get things like this done.”

A major obstacle to TBO deployment is a lack of financial commitment from airlines still dealing with COVID-19 losses. This gap between theory and practice is nothing new: “The supplier-side of the aviation industry is brilliant at coming up with innovative technological solutions,” said Bryan. “Unfortunately, most of it is developed in a vacuum with respect to the airlines’ business-driven requirements.”

Nations who have suffered economically due to the pandemic may also be hesitant to adopt TBO, opting to allocate scarce public funds to other more pressing (and publicly popular) projects. Some of them may also fear TBO’s geopolitical implications. Under such a trans-border scheme, “It will be entirely possible for more prominent, adjacent states to extend a high-level TBO-centric overlay above smaller states,” Bryan explained. “Some may not wish to yield ‘control’.”

This said, the biggest challenge to implementing TBO may be the fact that the initiative is being driven by ICAO and air traffic management, rather than IATA and airlines. Right now “IATA is confused about what TBO is, what it means to them and their members, and what they should be doing about it,” said Bryan. “Although no one in IATA appears to recognize it, airlines need IATA to build the industry-wide frameworks and implementation projects necessary to achieve TBO. This is because TBO is not a technology project for individual airlines to implement. It is a business program that will bring a paradigm shift to the way all airlines operate.”

An Unavoidable Necessity

Even with the drop caused by COVID-19, global air traffic is destined to keep growing with more kinds of aerial vehicles trying to share the same finite airspace.

This inescapable fact explains why the adoption and implementation of TBO is an unavoidable necessity for global aviation.

“Do we need TBO? Absolutely. There is no alternative,” said Hof. “Unless a Star Trek-like transporter is invented or a global hyperloop network is built, there is simply no other choice,” Bryan agreed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.